National Restaurant Association of India & Ors. Vs Union of India & Anr

Date: March 27, 2025

Court: High Court

Bench: Delhi

Type: Writ Petition

Subject Matter

Restaurant service charge collections can only be voluntary and must be distinctly separated from food pricing

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

1. This hearing has been done through hybrid mode.

2. Whether the collection of mandatory Service Charge by restaurants and other establishments is permissible under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 (hereinafter, the ‘CPA, 2019’)?

Background:

3. The Central Consumer Protection Authority (‘CCPA’) established under Section 10 of the CPA, 2019 received several complaints regarding restaurants and hotels (hereinafter, the ‘restaurant establishments’) charging ‘Service Charge’ over and above the cost of the food items. This Charge in the range of 5-20% in lieu of ‘Tip’ or ‘Gratuity’, was being collected from consumers on a compulsory basis. In addition, Goods and Services Tax (‘GST’) was charged on the said service charge, resulting in substantial burden consumers. The CCPA then issued guidelines to prevent unfair trade practices and protect consumer interest with regard to levying of service charge, on 4th July, 2022. The same are extracted hereinbelow for ready reference:

“3. It has come to the notice of the CCPA through many grievances registered on the National Consumer Helpline that restaurants and hotels are levying service charge in the bill by default, without informing consumers that paying such charge is voluntary and optional. Further, service charge is being levied in addition to the total price of the food items mentioned in the menu and applicable taxes, often in the guise of some other fee or charge.

4. It may be mentioned that a component of service is inherent in price of food and beverages offered by the restaurant or hotel. Pricing of the product thus covers both the goods and services component. There is no restriction on hotels or restaurants to set the prices at which they want to offer food or beverages to consumers. Thus, placing an order involves consent to pay the prices of food items displayed in the menu along with applicable taxes. Charging anything other than the said amount would amount to unfair trade practice under the Act.

5. It is understood that a tip or gratuity is towards hospitality received beyond basic minimum service contracted between the consumer and the hotel management, and constitutes a separate transaction between the consumer and staff of the hotel or restaurant, at the consumer’s discretion. Only after completing the meal, a consumer is in a position to assess the quality and service and decide whether or not to pay tip or gratuity and if so, how much. The decision to pay tip or gratuity by a consumer does not arise merely by entering the restaurant or placing an order. Therefore, service charge cannot be added in the bill involuntarily, without allowing consumers the choice or discretion to decide whether they want to pay such charge or not.

6. Further, any restriction of entry based on collection of service charge amounts to a trade practice which imposes an unjustified cost on the customer by way of forcing him/her to pay service charge as a condition precedent to placing order of food and beverages, and falls under restrictive trade practice as defined under Section 2 (41) of the Act.

7. Therefore, to prevent unfair trade practices and protect consumer interest with regard to levying of service charge, the CCPA issues the following guidelines –

(i) No hotel or restaurant shall add service charge automatically or by default in the bill.

(ii) Service charge shall not be collected from consumers by any other name.

(iii) No hotel or restaurant shall force a consumer to pay service charge and shall clearly inform the consumer that service charge is voluntary, optional and at consumer’s discretion.

(iv) No restriction on entry or provision of services based on collection of service charge shall be imposed on consumers.

(v) Service charge shall not be collected by adding it along with the food bill and levying GST on the total amount.

8. The aforementioned guidelines shall be in addition to and not in derogation of the guidelines dated 21.04.2017 published by the Department of Consumer Affairs.

9. If any consumer finds that a hotel or restaurant is levying service charge in violation to the above mentioned guidelines, a consumer may:-

(i) Make a request to the concerned hotel or restaurant to remove service charge from the bill amount.

(ii) Lodge a complaint on the National Consumer Helpline (NCH), which works as an alternate dispute redressal mechanism at the pre-litigation level by calling 1915 or through the NCH mobile app.

(iii) File a complaint against unfair trade practice with the Consumer Commission. The Complaint can also be filed electronically through e-daakhil portal www.edaakhil.nic.in for its speedy and effective redressal.

(iv) Submit a complaint to the District Collector of the concerned district for investigation and subsequent proceeding by the CCPA. The complaint may also be sent to the CCPA by e-mail at com-ccpa@nic.in.” s

4. In effect the above guidelines prescribed as under –

- That restaurant establishments are prohibited from adding service charge to the bills of the consumers automatically or by default;

- That payment of service charge cannot be forced by such establishments and it ought to be made optional.

- That consent for payment of service charge cannot be made a basis for permitting entry of consumers into the restaurant establishments;

- That no GST can be charged on the service charge amount.

- That service charge shall not be collected from consumers by any other name.

The above guidelines are under challenge in these two petitions.

Facts:

5. The first petition being W.P.(C) 10683/2022 is filed by the National Restaurants Association of India (‘NRAI’) through its Secretary General, along with two other office bearers. The second petition being, W.P.(C) 10867/2022 has been filed on behalf of the Federation of Hotels and Restaurants Association of India (‘FHRAI’) along with two members as co-Petitioners.

6. The Petitioners, vide the present petitions, inter alia seek issuance of an appropriate writ under Article 226 of the Constitution of India quashing/setting-aside of the guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 issued by the CCPA.

7. The Petitioners together, claim to represent the interest of a substantial number of restaurant establishments across the country. NRAI is stated to be an association of restaurant owning companies and other entities which own restaurants and other food establishments. As per the writ petition, NRAI claims that it represents the voice of the restaurant industry as it represents lakhs of restaurants in India. According to the Association, it has 7,000 restaurants in India and 2,500 member outlets in the Delhi NCR.

8. FHRAI is an organization which, according to the writ petition, represents the interest of 55,000 hotels and 5,00,000 restaurants across the country.

9. The facts that can be gleaned from both the petitions are that on 14th December, 2016 the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution had issued a letter regarding levy of service charge by hotels and restaurants to the Secretary, Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Protection of all States and Union Territories. The said letter is extracted hereinunder for a ready reference:

“Sir/Madam,

I am directed to say that it has come to the notice of this Ministry through a number of complaints from consumers received in the National Consumer Helpline that hotels and restaurants are following the practice of charging ‘service charge’ in the range of 5-20%, in lieu of tips. A consumer is forced to pay this charge irrespective of the kind of service provided to him. The consumers are also required to pay service tax on this service charge so collected by the hotels and restaurants.

2. The Consumer Protection Ac, 1986 provides that a trade practice which, for the purpose of promoting the sale, use or the supply of any goods or for the provision of any service, adopts any unfair method or deceptive practice, is to be treated as an unfair trade practice. The said Act further provides that a consumer can make a complaint to the appropriate consumer forum established under the Act against

(i) an unfair trade practice adopted by any trader or service provider

(ii) the services hired or availed of, suffered from deficiency in any respect (iii) a trader or service provider, as the case may be, has charged for the goods or for the services a price in excess of the price. (a) fixed by or under any law for the time being enforce. (b) displayed on the goods or any package containing such goods, (c) displayed on the price list exhibited by him or under any law for the time being in force or (d) agreed between the parties.

3. The Hotel Association of India. Bhikaji Cama Place, New Delhi, on the matter being taken up with them, observed that the service charge is completely discretionary. Should a customer be dissatisfied with the dining experience he/she can have it waived off. Therefore, it is deemed to be accepted voluntarily.

4. In the circumstances, it is requested that the State Government may sensitize the companies, hotels and restaurants in the state regarding aforementioned provisions of the Consumer Protection Act, Information may also be disseminated through display at the appropriate place in the hotel/restaurants that the ‘service charges” are discretionary/ voluntarily and a consumer dissatisfied with the services can have it waived off.

5. Further, a number of consumers have also submitted complaints to the effect that most of the retail outlets do not issue a bill to the consumer in respect of the goods bought by him. The consumer has a right to a bill for the goods bought by him. The State Government may also issue instructions to the retail outlets in the state to invariably issue a bill to a consumer for the purchases made by him.”

10. As per the above letter, the Ministry, while taking cognizance of the collection of Service Charge, relied upon the stand of the Hotel Association of India that the payment of the said charge is discretionary. The Ministry thus instructed the Secretary, Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Protection of all States and Union Territories, that this position be publicised and information be disseminated to the effect that service charge can be waived off.

11. In effect, the said letter recognised that payment of service charge, charged by the restaurant establishments is within the discretion of the consumer and waiver can be sought.

12. Pursuant to the letter dated 14th December, 2016 an advisory was issued by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution on 2nd January, 2017 to the effect that service charge is a voluntary charge that can be waived off by a consumer, dissatisfied with the service of the restaurant establishment. The relevant portion of the same is extracted hereinunder:

“The Department of Consumer Affairs has asked the State Governments to sensitize the companies, hotels and restaurants in the states regarding aforementioned provisions of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 and also to advise the Hotels/Restaurants to disseminate information through display at the appropriate place in the hotels/restaurants that the ‘service charges’ are discretionary/ voluntary and a consumer dissatisfied with the services can have it waived off.”

13. A reply to the letter dated 14th December, 2016 and the advisory published on 2nd January, 2017 by the Department of Consumer Affairs was sent by the NRAI to the Department of Consumer Affairs on 4th January, 2017. However, on 21st April, 2017 an advisory was again issued by the Department of Consumer Affairs, inter alia, stating that service charge is to be paid at the discretion of the customer. The relevant portion of the same is extracted hereinunder:

“GUIDELINES ON FAIR TRADE PRACTICES RELATED TO CHARGING OF SERVICE CHARGE FROM CONSUMERS BY

HOTELS/RESTAURANTS

Whereas, the Department of Consumer Affairs. Government of India is mandated to ensure that consumers are protected as per the provisions of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 (hereinafter referred as ‘The Act’);

Whereas, a customer visiting a hotel or restaurant for availing its hospitality, which includes buying the food & beverages and availing services connected therewith or incidental thereto for consideration, falls under the definition of consumer as per the Act;

Whereas, it has come to the notice of this Department that some hotels and restaurants are charging tips/gratuities from the customers without their express consent in the name of service charges;

Whereas, it has also come to the notice of this Department that some customers have been paying tips to waiters in addition to service charges under the mistaken impression that service charge is a part of taxes;

Whereas, it has also come to the notice of this Department that in some cases hotels/restaurants are restraining customers from entering the premises if they are not in prior agreement to pay the mandatory service charge:

Whereas, public interest has arisen due to a number of grievances reported against mandatory levy of service charges by the hotels and restaurants;

Now therefore, the Government considers it appropriate to clearly distinguish between the fair and unfair trade practices in respect of service charges, charged by the hotels/restaurants. and issues the following guidelines:

(1) A component of service is inherent in provision of food and beverages ordered by a customer. Pricing of the product therefore is expected to cover both the goods and service components.

(2) Placing of an order by a customer amounts to his/her agreement to pay the prices displayed on the menu card along with the applicable taxes. Charging for anything other than the afore-mentioned, without express consent of the customer, would amount to unfair trade practice as defined under the Act.

(3) Tip or gratuity paid by a customer is towards hospitality received by him/her, beyond the basic minimum service already contracted between him/her and the hotel management. It is a separate transaction between the customer and the staff of the hotel or restaurant. which is entered into at the customer’s discretion.

(4) The point of time when a customer decides to give a tip/gratuity is not when he/she enters the hotel/restaurant and also not when he/she places his/her order. It is only after completing the meal that the customer is in a position to assess quality of service, and decide whether or not to pay a tip/gratuity and if so, how much. Therefore, if a hotel/restaurant considers that entry of a customer to a hotel/restaurant amounts to his/her implied consent to pay a fixed amount of service charge, it is not correct. Further, any restriction of entry based on this amounts to a trade practice which imposes an unjustified cost on the customer by way of forcing him/her to pay service charge as condition precedent to placing order of food and beverages. and as such it falls under restrictive trade practice as defined under section 2(1)(nnn) of the Act

(5) In view of the above, the bill presented to the customer may clearly display that service charge is voluntary, and the service charge column of the bill may be left blank for the customer to fill up before making payment.

(6) A customer is entitled to exercise his/her rights as a consumer, to be heard and redressed under provisions of the Act in case of unfair/restrictive trade practices and can approach a Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission/Forum of appropriate jurisdiction.”

14. On 20th May, 2022 the Department of Consumer Affairs sent a letter to the President, NRAI informing that a meeting will be conducted on 2nd June, 2022 to discuss the nature of implementation of service charge in the restaurant establishments of India. The same is extracted hereunder for ready reference:

“It has come to my attention through media reports and grievances registered by consumers on the National Consumer Helpline (NCH) that restaurants and eateries are collecting service charge from consumers by default, even though collection of any such charge is voluntary and at the discretion of consumers and not mandatory as per law.

2. Due to this, consumers are forced to pay service charge, often fixed at arbitrarily high rates by restaurants. Consumers are also being falsely misled on the legality of such charges and harassed by restaurants on making a request to remove such charges from the bill amount

3. it is relevant to mention that the Department of Consumer Affairs has already published guidelines dated 21.04.2017 on charging of service charge by hotels/restaurants. The guidelines note that entry of a customer in a restaurant cannot be itself be construed as a consent to pay service charge. Any restriction on entry on the consumer by way of forcing her/him to pay service charge as a condition percent to placing an order amounts to ‘restrictive trade practice’ under the Consumer Protection Act.

4. In this regard, the Department of Consumer Affairs is holding a meeting on 2nd June, 2022 at 1200 Hrs to discuss the following issues affecting consumers in India:-

- Making service charge compulsory by hotels/restaurants

- Adding service charge in the bill in the guise of some other fee or charge.

- Suppressing from consumers that paying service charge is optional and voluntary.

- Embarrassing consumers in case they resist from paying service charge

- Making service charge compulsory by hotels/restaurants

- Adding service charge in the bill in the guise of some other fee or charge.

- Suppressing from consumers that paying service charge is optional and voluntary.

- Embarrassing consumers in case they resist from paying service charge

5. Since this issue impacts consumers at large on a daily basis and has significant ramification on the rights of consumers, it is necessary that it is examined with closer scrutiny and detail. Therefore, you are requested to attend the meeting as per the above-mentioned schedule.”

15. On 23rd May, 2022 the Department of Consumer Affairs issued a press release, wherein a meeting was called by the Department with stakeholders to discuss the levying of service charge by the restaurant establishments. The said circular is extracted below:

“The Department of Consumer Affairs (DoCA) has scheduled a meeting on 2nd June, 2022 with the National Restaurant Association of India to discuss the issues pertaining to Service Charge levied by restaurants. The meeting follows as a result of DoCA taking notice of a number of media reports as well as grievances registered by consumers on the National Consumer Helpline (NCH). In a letter written by Shri Rohit Kumar Singh, Secretary, Department of Consumer Affairs to President, National Restaurant Association of India, it has been pointed out that the restaurants and eateries are collecting service charge from consumers by default, even though collection of any such charge is Voluntary and at the discretion of consumers and not mandatory as per law.

It has been pointed out in the letter that the consumers are forced to pay service charge, often fixed at arbitrarily high rates by restaurants. Consumers are also being falsely misled on the legality of such charges and harassed by restaurants on making a request to remove such charges from the bill amount. “Since this issue impacts consumers at large on a daily basis and has significant ramification on the rights of consumers, the department construed it necessary to examine it with closer scrutiny and detail”, the letter further adds.

The following issues pertaining to complaints by consumers would be discussed during the meeting.

- Restaurants making service charge compulsory

- Adding service charge in the bill in the guise of some other fee or charge.

- Suppressing from consumers that paying service charge is optional and voluntary.

- Embarrassing consumers in case they resist from paying service charge.

- Restaurants making service charge compulsory

- Adding service charge in the bill in the guise of some other fee or charge.

- Suppressing from consumers that paying service charge is optional and voluntary.

- Embarrassing consumers in case they resist from paying service charge.

It is relevant to mention that the Department of Consumer Affairs has already published guidelines dated 21.04.2017 on charging of service charge by hotels/restaurants. The guidelines note that entry of a customer in a restaurant cannot be itself be construed as a consent to pay service charge. Any restriction on entry on the consumer by way of forcing her/him to pay service charge as a condition percent to placing an order amount to ‘restrictive trade practice’ under the Consumer Protection Act.

The guidelines clearly mention that placing of an order by a customer amount to his/her agreement to pay the prices displayed on the menu card along with the applicable taxes. Charging for anything other than the afore- mentioned. without express consent of the customer, would amount to unfair trade practice as defined under the Act.

As per the guidelines, a customer is entitled to exercise his/her rights as a consumer to be heard and redressed under provisions of the Act in case of unfair/restrictive trade practices. Consumers can approach a Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission / Forum of appropriate jurisdiction.”

16. Further to the letter dated 20th May, 2022 and the press release dated 23rd May, 2022, a meeting was conducted by the Ministry with the stakeholders on 2nd June, 2022. On the said date, FHRAI made a representation to the Department of Consumer Affairs wherein, it explained the significance of service charge for the hospitality sector.

17. The Department of Consumer Affairs, then issued a press release dated 2nd June 2022, inter alia stating that the framework of service charge, as charged by the restaurant establishments requires a complete overhaul so as to ensure strict compliance by the stakeholders concerned with regard to the nature of levying service charge by the establishments.

18. On 4th July, 2022 the impugned guidelines were then issued by CCPA inter alia clarifying the nature of implementation of the service charge. The relevant portion of the Guidelines are extracted above in paragraph 3.

19. Further, on 6th July, 2022 the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and

Public Distribution issued a communication to the District Collectors of all States and Union Territories inter alia intimating them that levying of service charge in violation of the guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 would be an unfair trade practice under the contours of the CPA, 2019. The communication dated 6th July, 2022 is extracted hereinunder for ready reference:

“As you might be aware, the Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA), has recently issued guidelines under Section 18(2)(1) of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 (” hereinafter called the Act”) to prevent unfair trade practices and protection of consumer interest with regard to levy of service charge in hotels and restaurants. The guidelines came into effect from 04.07.2022, i.e., on the day they were issued. The guidelines are attached as Annexure – I.

2. The guidelines stipulates the following:

- Hotels or restaurants shall not add service charge automatically or by default in the food bill.

- No collection of service charge shall be done by any other name.

- No hotel or restaurant shall force a consumer to pay service charge and shall clearly inform the consumer that service charge is voluntary, optional and at consumer’s discretion.

- No restriction on entry or provision of services based on collection of service charge shall be imposed on consumers.

- Service charge shall not be collected by adding it along with the food bill and levying GST on the total amount.

- Hotels or restaurants shall not add service charge automatically or by default in the food bill.

- No collection of service charge shall be done by any other name.

- No hotel or restaurant shall force a consumer to pay service charge and shall clearly inform the consumer that service charge is voluntary, optional and at consumer’s discretion.

- No restriction on entry or provision of services based on collection of service charge shall be imposed on consumers.

- Service charge shall not be collected by adding it along with the food bill and levying GST on the total amount.

3. The guidelines include the actions that consumers can take in case of a violation of the guidelines by hotels/restaurants, including submission of a complaint to the District Collector of the concerned district for investigation and subsequent proceeding by the CCPA. 4. It may be mentioned that under Section 17 of the Act, a complaint relating to violation of consumer rights or unfair trade practices which is prejudicial to the interests of consumers as a class may be forwarded in writing or in electronic mode to the District Collector. Further, under Section 16 of the Act, on a complaint or on a reference made to him by the Central Authority, the District Collector may inquire into or investigate complaints regarding violation of rights of consumers as a class within his jurisdiction and submit his report to CCPA.”

20. According to the Petitioners, the impugned guidelines issued by the CCPA are violative of the rights of its members. Accordingly, it is prayed that the guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 read along with the communication issued on 6th July, 2022 by the CCPA to all the District Collectors be set aside. Brief Case of the Petitioners:

21. The brief case of the Petitioners is that the impugned guidelines are arbitrary, untenable and are liable to be set aside. The stand of both the Petitioners is that the collection of service charge has been prevalent in the hospitality industry for more than 80 years and the same is valid as there exists no law that prohibits the Petitioners from charging the same.

22. Sometime in 2016, the Department of Consumer Affairs had issued a letter dated 14th December, 2016, as per which, information was directed to be disseminated that the payment of service charge is discretionary and voluntary at the behest of the consumer and that the same can be waived off if the consumer is dissatisfied with the service. This was followed by another advisory by the Department of Consumer Affairs dated 21st April, 2017 wherein again the Department sought to direct that the bills raised by establishments ought to display clearly in the menu card that payment of service charge is voluntary.

23. According to the Petitioners, after the advisory dated 21st April, 2017, the Petitioners and their members continued to collect service charge from consumers. It is their case that service charge is recognized as valid, in various decisions. Further, the CCPA has no power or jurisdiction under the CPA, 2019 to issue such guidelines which impinge upon the Petitioners’ rights to carry on their businesses as provided under Articles 14 and 19 of the Constitution of India.

24. It is further, the case of the Petitioners, that the levy of service charge is purely the discretion of the management of the establishment. The said charges are used for the benefit of staff, labour, utility workers, backend workers, etc. As per the law laid down in the Constitution of India, the Government has no authority to interfere in the decision of the owner of the establishment to levy service charge, which is prevalent in most countries in the world. The same has also been recognized by the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission, New Delhi and other Courts as well as in various decisions. Hence, the guidelines are contrary to law and deserve to be quashed.

Proceedings in the present writ petitions:

25. Notice in the NRAI writ (supra) was issued on 20th July, 2022. On the said date, the Court had prima facie come to the conclusion that the directions contained in paragraph 7 of the guidelines shall remain stayed, subject to certain conditions. The operative portion of the said interim order is set out below:

“9. The matter requires consideration. Consequently, and till the next date of listing the directions as contained in paragraph 7 of the impugned Guidelines of 04 July 2022 shall remain stayed subject to the following conditions:-

(1) The members of the petitioner Association shall ensure that the proposed levy of a service charge in addition to the price and taxes payable and the obligation of customers to pay the same is duly and prominently displayed on the menu or other places where it may deemed to be expedient.

(2) The members of the petitioner Association further undertake not to levy or include service charge on any “take away” items.

26. The said interim order was challenged before the ld. Division Bench, which, vide order dated 18th August, 2022 directed as under:

“Learned Additional Solicitor General has vehemently argued before this Court that practically no opportunity for filing reply was granted to the Union of India, and an interim order has been passed by the Learned Single Judge. The interim order deserves to be set aside. He has argued the matters on the merits also but the fact remains that there was no reply before the Learned Single Judge either to the Applications for grant of interim relief or to the main Writ Petitions. Therefore, without averting to the merits of the case, liberty is granted to the Union of India to file a reply to the Application for grant of interim relief as well as to the main Writ Petition, and they shall certainly be free to file an Application for vacating the stay in the petitions as well.

The Office is directed to list the matters i.e. W.P.(C) No. 10683/2022 and W.P.(C) No. 10867/2022 immediately after 10 days before the Learned Single The Leamed Single Judge is requested to pass appropriate order in respect of the Application for vacating Stay/ Final Hearing in accordance with law without being influenced by the interim order passed by him.”

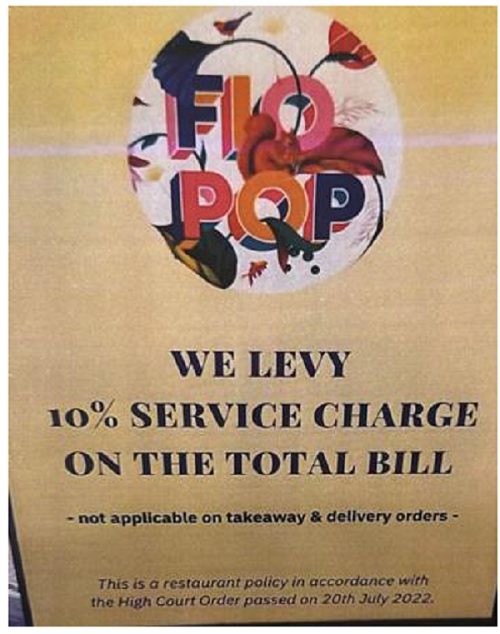

27. On 15th February, 2023, certain practices adopted by the restaurant establishments were brought to the notice of the Court wherein the stand of the Respondents was that the interim order dated 20th July, 2022 was being used by the restaurant establishments, as the basis for charging service charge, by displaying it both, in the menu card as also the display boards outside their establishments. To substantiate this stand, the Respondents have placed on record a sample image of a restaurant establishment following this practice. The same is extracted hereinbelow for ready reference:

28. Certain examples of restaurant establishments such as the Punjab Grill, The Beer Cafe, The Urban Foundry & Distillery, etc. were cited before the Court to show how the restaurant establishments were using the interim order dated 20th July, 2022, as the basis for charging service charge. Grievances raised by consumers, pertaining to the same were registered in the National Consumer Helpline from 21st July,2022 to 29th October, 2022. The same are extracted hereinunder for a ready reference:

“1. Punjab Grill Responds as “It is wrong to state that the service charge is charged without the customer consent and customer is forced to pay the same. It is very clearly mentioned in our menu cards that we charge service charge and if the customer asks us to remove the said service charge component from the bill than we happily remove the same. But the customer paid the bill without any protest or demur on service charge and with his consent. Please note, Hon’ble Delhi High Court on 20th July, 2022, stayed the guidelines issued by CCPA dated 4th July 2022 on service charge and levying service charge by restaurants is completely legal, if prominently mentioned on the Menu Cards. Therefore, service charge is not charged illegally and is as per the norms issued by the Government.

2. The Beer Cafe Responds as “In line with the directions of the Hon’ble Court of Delhi as per order dated 20.07.2022, BTB Marketing Private Limited has complied with the guidelines laid down for all the restaurants in PARA 9 of the order. We have mentioned prominently on our menu and we have also put up stickers everywhere in our premises, where it is expedient to be seen by the customer, that We levy 10% Service Charge. Please note that the same order has put a stay on the order of the CCPA dated 4th July, 2022.

3. The Urban Foundry Respond as “Sir, Information regarding levying of service charge is listed on the menu as well as at prominent place in the restaurant. the Hon. Delhi high court order court no w.p.(c) 10683/2022 CM, APPL 31033/2022 Dt. 20.07.2022 which was shown, it lists the guidelines for levying the charge & information around the same. The guest was informed about the same before levying the charge.

4. Distillery Responds as “it is submitted that we levy a 10% service charge on all invoices. The said charge ensures well being of our staff which diligently serves the consumers at the cafe. The said levy of service charge @ 10% has been priorly intimated to the consumers by way of specific mention on our menu card (reference picture attached) and the said charge is not hidden at the time of placing of an order by the consider and the consumer willing and consciously makes a choice of ordering from the menu despite knowing the fact that we levy service charge mandatorily. The said levy is also in line with the interim order passed by the Hon’ble High Court, Delhi allowing restaurants to collect service charges by way of prior intimation to the consumers.

5. Vapour Pub & Brewery Respond as “Our policy was clear. If a guest asks for service charge removal we should remove it without question. Now attached an article of high court stay and say the matter is sub-judice and appropriate course of action will be followed as per directions of the Honourable court”

29. Considering these submissions, on 12th April, 2023, a detailed order was passed to the following effect:

“9. Considering the submissions made and the concerns raised on both sides, the following directions are issued:

i. At the outset, it is noticed that both these petitions have been preferred by associations/federations of hotels and restaurants. In order to have clarity as to the members qua whom the present writ petitions have been preferred, taking into consideration, orders passed in WP(C) 3324/1999 titled ‘Kuber Times Emp. Assn. v. State & Ors.’, both the associations/federations shall file a complete list of all their members who are supporting the present writ petitions. The said list shall be filed by 30th April 2023. The Registry to compute the court fee which would be payable, which shall also be informed to the Petitioners. The necessary court fee shall then be deposited by the Petitioners.

ii. Ld. counsels for the associations/federations have submitted that they have lakhs of members. In view of the fact that both these associations/federations have preferred these writ petitions, this Court is of the opinion that the associations/federations ought to consider the following aspects and place their stand before the Court:

a. The percentage of members of the Petitioners who impose service charge as a mandatory condition in their bills.

b. Whether the said members and the associations/federations would have any objection in the term `Service Charge’ being replaced with alternative terminology so as to prevent confusion in the minds of the consumer that the same is not a Government levy. Some terminologies that could be considered are ‘Staff welfare fund’, ‘Staff welfare contribution’, ‘Staff charges’, ‘Staff welfare charges’, etc. or any other alternative terminology.

c. The percentage of members who are willing to make service charge as voluntary and not mandatory, with option being given to the consumers to make their contribution to the extent that they are voluntarily willing subject to a maximum percentage that may be charged.”

30. As can be seen from the above order, the Petitioners were directed to give a complete list of their members and further details regarding the percentage of members of the Petitioners who impose service charge as a mandatory condition in their bills. Certain alternative terminology, to be used in place of ‘service charge’ was also suggested.

31. Pursuant to the above order, affidavits were filed by NRAI and FHRAI. On 5th September, 2023 the Court perused the said affidavits, and recorded the following facts:

“5. Ld. Counsels for both the Petitioners claim that the affidavits in terms of the order dated 12th April, 2023 have been placed on record by the National Restaurant Association of India (‘NRAI’) and Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations of India (‘FHRAI’). The position that emerges after a perusal of the said affidavits is as under:

(i) Insofar as the NRAI is concerned, as per the affidavit filed by Mr. Prakul Kumar, Secretary General of NRAI, there are a total of about 1100 members, whose list has been placed on record. As per the said affidavit, 80% of the NRAI members impose service charge on the customers as a mandatory condition. In the said affidavit, it has been stated that the members of NRAI are not willing to change the terminology from ‘Service Charge’ to any of the alternatives proposed by the Court as put to them in the order dated 12th April, 2023. The minutes of the meeting of the Managing Committee dated 18th April, 2023 of NRAI reveals that the conclusion that the said association has reached that the terminology of service charge cannot be changed. It is further claimed in the said affidavit by the NRAI that there is also no scope of confusion between the terms ‘Service Tax’ and ‘Service Charge’ as the Service Tax is no longer being imposed by restaurants and hotels.

(ii) Insofar as FHRAI is concerned, the list of members that has been placed on record is totalling to 3327 members. As per the affidavit filed by Mr. Jaison Chacko – Secretary General of FHRAI, amongst the members of FHRAI, there is no uniformity or consistency being followed in respect of ‘Service Charge’ – some members charge ‘Service Charge’ and some do not. However, it is specifically stated that the members who are charging Service Charge, charge the same compulsorily from their customers and do not give an option of paying the same or not.”

32. The Court then, on 5th September, 2023 crystallized the issues for determination as under:

“ 8. In the opinion of this Court, there are four major issues which need to be considered –

(i) Whether the CCPA can issue the impugned directions to hotels and restaurants;

(ii) Whether hotels and restaurants can `levy’ service charge on customers;

(iii) Whether the service charge can be made compulsorily payable by customers;

(iv) Whether the said amount collected can be called `Service Charge’.”

33. On the said date, it was also clarified on behalf of the FHRAI that its members are willing to change the terminology with respect to the restaurant establishments collecting a charge on service provided. It was submitted that the members of FHRAI are willing to change the terminology from ‘Service Charge’ to ‘Staff Contribution’. The relevant portion of the order dated 5th September, 2023 is recorded hereinunder:

“9. Insofar as the FHRAI is concerned, the submission of ld. Sr. Counsel on behalf of FHRAI that its members are willing to change the terminology from ‘Service Charge’ to ‘Staff Contribution’ is recorded. Henceforth, the said terminology shall be used by FHRAI’s members who are collecting the same. However, Mr. Bhasin, ld. Counsel submits that the members of NRAI are not willing to change the terminology from ‘Service Charge’ to any other terminology. The stand of NRAI is that the ‘Service Charge’ which is being imposed currently, has been considered in a number of decisions and thus, the same would require consideration.”

34. As recorded in the order dated 5th September, 2023, the FHRAI made a submission that its members are willing to change the terminology for charging their customers for service, from ‘service charge’ to ‘staff contribution’. However, NRAI was not willing to make the said change. On the said date, therefore, the following observations were made:

“10. At this stage, the Court notes that it is already 4:45 pm. The matter would now require to be heard further. However, considering that the issues raised would affect customers across the country, the matter would be taken up expeditiously. In view of the submissions made in Court today as also in the affidavits by the two associations, in the meantime, while the Court considers this petition, the following interim directions are issued:

(i) That the members of FHRAI, who are collecting the charges, shall with immediate effect cease the usage of the term ‘Service Charge’ and only use the terminology ‘Staff Contribution’ for the amount being charged as ‘Service Charge’ currently;

(ii) The said amount being charged as ‘Staff Contribution’ by members of FHRAI shall not be more than 10% of the total bill amount excluding the GST component;

(iii) In case of establishments mentioned in (i) above, the menu cards shall specify in bold that after the payment of ‘Staff Contribution’, no further tip is necessary to be paid to the establishment/servers/restaurant staff;

11. The above is merely an interim order and directions, which shall be subject to further orders in the writ petitions. The above order shall not be construed as an approval of the charges being collected, in as much as the legality of the collection of such charges is to be adjudicated by this Court.”

35. The matter was then taken up on 11th March, 2024. During the course of arguments on 11th March, 2024, it was brought to the notice of the Court that the FHRAI in its representation dated 24th June, 2022 had clearly taken a stand that service charge payment is the prerogative of the customer or the guest. Ld. Counsel for FHRAI was therefore directed to seek instructions in this regard. The relevant portion of the said order is set out below:

“7. Today, Mr. Parekh, ld. Counsel has continued his submissions. During his submissions, it has been his stand that once a customer is informed of the payment of service charge, the same would be compulsorily payable. After the customer has entered the premises and has availed of the services, there is no option for the customer but to pay. This position is countered by Mr. Sandeep Kumar Mahapatra and Mr. Kirtiman Singh, the ld. CGSCs for the Union of India who rely upon the representation dated 24th June, 2022 issued by the FHRAI to the Minister of Tourism and Culture, where the stand taken is that service charge is in the nature of a tip or a gratuity and it is the prerogative of the customer whether to pay it or not. The relevant extracts of the representation dated 24th June, 2022 made by FHRAI are set out below:

“In simple words, the Service Charge is an amount that is added to customer’s bill in a restaurant to pay for the services of the persons who are involved in serving the food on the table. It is also colloquially known as “tip” or “gratuity”. A Service Charge is a solicitation of a nominal additional charge for providing a delightful and memorable experience to the customers.

xxx xxx xxx

However, Service Charge of a restaurant is a voluntary fee paid by the customer which is disclosed well in advance before placing an order. Also, the same is clearly included as a separate heading in the bill as a “Charge”, and not as a “Tax”. Service Charge is neither a hidden charge nor a compulsory fee in any guise as the restaurants maintain utmost transparency with regard to the amount, the rate and the purpose of the charge. It is shown separately in the final bill and payment of the same is up to the prerogative of customer / guest.”

8. In response to the above reference to the representation of FHRAI, Mr. Parekh, ld. Counsel submits that his client’s stand ought to be considered from the representation dated 2nd June, 2023. However, he would like to seek instructions insofar as the representation 24th June, 2022 is concerned.”

36. An affidavit was thereafter filed on 10th April, 2024. The same was taken on record on 23rd April, 2024. On the said date, Mr. Jaison Chacko, Secretary General of the FHRAI was present in Court. He confirmed that the signatory of the letter dated 24th June, 2024 i.e., Mr. Gurbaxish Singh Kohli was the Vice-President of the FHRAI for a period of four years. It was confirmed that he had signed the said letter. However, the stand of the FHRAI was that the statements made in the said letter ought not to be taken in isolation.

37. Thereafter, the matters were heard from time to time. Submissions made by counsel for the parties are recorded as under: –

Submissions on behalf of the Petitioners:

38. Ld. Counsels – Mr. Lalit Bhasin and Mr. Sameer Parekh, appearing on behalf of the Petitioners submit as under:

38.1. The impugned guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 issued by the CCPA impinge upon the rights of the Petitioners guaranteed under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India inasmuch as it interferes with the right to trade which is conferred upon the owners of such establishments.

38.2. The establishment ought to have the freedom to price its goods in the manner it chooses, either by setting a price for the food product itself or by distributing the cost between the price of the food product and the service charge.

38.3. So long as the customer of such establishment is informed that the payment of service charge is compulsory, by way of displaying it both on the menu car as also the display board, it becomes a contractual issue between the restaurant establishment and the consumer.

38.4. The service charge component is a major component in the negotiation of wages with the employees of these establishments and, thus, the same ought not to be interfered with in this manner by the Authority established under the CPA, 2019.

38.5. Reference has been made to Sections 10, 15, 16, 18, 20, 21 & 24 of the CPA, 2019 to submit that the impugned guidelines have been issued under Section 18 of the act without affording a preliminary hearing. It is, however, admitted that there was a stakeholder consultation prior to the issuance of the guidelines.

38.6. Reference is made to Section 20 of the CPA, 2019 to argue that in cases wherein the CCPA is of the opinion that any trade practice is unfair or prejudicial to consumer interest, a proper hearing must be given by the said Authority, which would then be appealable to the National Commission under Section 24 of the CPA, 2019. The CCPA, in the present case, has not followed this process and thus there is violation of the principles of natural justice.

38.7. The impugned guidelines are operating in rem and not qua any category of restaurant establishments.

38.8. For the guidelines to have teeth, the impugned guidelines ought to have been enacted in the form of a law, either as a rule or as a regulation by the Central/State Government. Further, the CCPA has also not placed the same before the Parliament under Sections 101, 102, 104 and 105 of the CPA, 2019 and thus, the impugned guidelines have no mandate as per law.

38.9. The CCPA, by simply publishing the guidelines through a notification and further issuing directions to District Collectors, is in contravention of the law. The said Authority has overreached its mandate under the scheme of the CPA, 2019. To circumvent the proper process for enacting a law, rule, or regulation, the Respondent has adopted this indirect method.

38.10. The aspect of service charge being imposed is a practice which has been continuing for the last 80 to 90 years. It has been repeatedly recognized by the Supreme Court and High Courts in various judicial decisions. The rationale behind imposing service charge or levying a service charge is in order to ensure equitable distribution of the tip amount which is paid by the consumer. So long as the menu of the restaurant establishment informs the customer prior to placing an order about the service charge, the service charge ought to be paid by the consumer.

38.11. Charges in the nature of service charge, have always been a matter of bargain and contract between management and the workmen. The charge is levied for the benefit of various workers and in fact, form part of the settlements which managements enter into with their workmen. Hence, the present matter is a contractual issue wherein the CCPA has no mandate.

38.12. The labour law jurisdiction is vested with the Labour Court, etc. which have repeatedly recognized service charge as being a component of charges collected by the management for the benefit of the workmen. The same is not governed by the CPA, 2019 but is part of the labour law jurisprudence. Further, settlements under the industrial disputes law are sacrosanct and any change brought about in this regard would affect a large number of establishments and the workmen with whom settlements have been entered into.

38.13. Reliance has been placed on a decision passed by the Supreme Court in Life Insurance Corporation of India v. D.J Bahadur (MANU/SC/0305/1980) to argue that settlements entered into between management and workmen are sacrosanct and an ordinance would not be operative so long as it is contrary to the settlement entered into. In this judgment, when an ordinance was issued in respect of bonus to be paid to the workmen, the Supreme Court held that the ordinance would not be operative as the same would be contrary to settlements which have been entered into by the management and the workmen.

38.14. The CCPA does not have the mandate to pass the impugned guidelines. Specific reference is made to paragraph 7 of the impugned guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 which prohibits automatic addition of service charge and states that service charge would not be collected by the establishments under any other name. Further, in paragraph 7.3, the guidelines state that service charge cannot be forced to be paid by the customer and that it should be made clear to the customer that the same is voluntary/optional at the discretion of the customer. These guidelines are entirely beyond the purview of the CCPA, as the definitions under the CPA, 2019 do not vest any such power in the CCPA to issue such guidelines. Reliance is placed upon Section 2(47) which defines unfair trade practices.

38.15. Service charge was a result of an expert committee report submitted by Mr. Diwan Chaman Lal, which recognized that service charges could be collected from consumers.

38.16. Reliance is placed upon Section 2(6) of the CPA,2019 to argue that if there is an agreement between the consumer and the establishment, there can even be no complaint against such an establishment.

38.17. There are broadly two types of service charges, one is a known service charge, and the other is an unknown service charge. Insofar as the unknown service charge is concerned, which is included into other aspects of the bill, the Petitioners do not support the same. The stand of the Petitioners is that so long it is announced clearly on the menu card/display board that a service charge will be levied, the consumer, by choosing to consume food and enjoy the experience, implicitly agrees to it. Thus, an implicit contract exists between the establishment and the consumer, which cannot be overridden. Moreover, this implicit contract cannot give rise to a complaint, in terms of Section 2(6)(iv) of the CPA, 2019.

38.18. There are a large number of restaurant establishments which are run in the country and in comparison, thereto, the complaints which are stated to have been received by the Respondent are few in number.

38.19. The NCDRC as also the MRTP Commission have dealt with this very issue in various judgments, wherein it has clearly been observed that service charge is a recognized mode of collecting amounts for the benefit of the workmen. Ld. Counsels submit that specialized Tribunals having already taken a view and permitting service charges to be collected, the CCPA’s jurisdiction would be completely untenable. Reliance is placed upon the following judgments to argue this proposition:

- Nitin Mittal vs. Pind Balluchi Restaurant (MANU/CF/0402/2012),

- S. S. Ahuja vs. Pizza Express (MANU/MR/0105/2001).

- The Rambagh Palace Hotel, Jaipur v. The Rajasthan Hotel

- Workers’ Union, Jaipur [(1976) 4 SCC 817]

- Management of Wenger and Co. v. Workmen. (AIR 1964 SC 86)

- Nitin Mittal vs. Pind Balluchi Restaurant (MANU/CF/0402/2012),

- S. S. Ahuja vs. Pizza Express (MANU/MR/0105/2001).

- The Rambagh Palace Hotel, Jaipur v. The Rajasthan Hotel

- Workers’ Union, Jaipur [(1976) 4 SCC 817]

- Management of Wenger and Co. v. Workmen. (AIR 1964 SC 86)

38.20. Reliance is also In Rajinder Kumar Jain v. ACIT, Circle 27(1) (MANU/ID/0193/2015) to argue that the recognized position in law is that the practice of payment of service charge to staff is not disputed by the revenue authorities.

38.21. To justify the extra charge collected by the restaurant establishments, reliance is placed on Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Association of India v. Union of India (UOI) and Ors. (MANU/SC/1624/2017). In this case, the question was whether the restaurant establishments could charge a higher price for bottled water dispensed by them. The Supreme Court inter alia observed that there is no bar on such sales. It is submitted that in the context of restaurant establishments, judicial recognition has been given to the fact that the food which is sold or the beverages which are made available are never considered to have been sold but are considered as a service and as part of the overall services which is provided to the customer. Thus, in the said case, the establishments were permitted to sell mineral water at prices which are higher than the Minimum Retail Price (‘MRP’).

38.22. Service charge is a valid component of charge collected from the customers for the benefit of employees and the workmen in the establishment. Service charge collected by the restaurant establishments has been recognised in various decisions:

- M/S Quality Inn Southern Star v. The Regional Director, Employees State, [(2014) 10 SCC 673]

- Gulf Co. Ltd. v. Union of India [(2014) 10 SCC 673]

- Commissioner of Income Tax v. ITC Ltd. [(2011) SCC OnLine Del 2215]

- ITC Limited Gurgaon v. Commissioner of I.T. (TDS) Delhi, AIR 2016 SC 2127

- The Rambagh Palace Hotel, Jaipur v. The Rajasthan Hotel Worker’s Union Jaipur, (supra)

- M/S Quality Inn Southern Star v. The Regional Director, Employees State, [(2014) 10 SCC 673]

- Gulf Co. Ltd. v. Union of India [(2014) 10 SCC 673]

- Commissioner of Income Tax v. ITC Ltd. [(2011) SCC OnLine Del 2215]

- ITC Limited Gurgaon v. Commissioner of I.T. (TDS) Delhi, AIR 2016 SC 2127

- The Rambagh Palace Hotel, Jaipur v. The Rajasthan Hotel Worker’s Union Jaipur, (supra)

38.23 On the strength of all these decisions, it is submitted that service charges are a part and parcel of running of a hospitality establishment especially once the menu card makes it clear that the establishment would be charging the service charge.

38.24.Mr. Bhasin, ld. Counsel emphasises that the interests of customers who can afford to pay the service charge must be balanced against the interests of the workmen, who are in a much more vulnerable position.

38.25.The next submission is that the trade and industry across the world recognizes service charge as a uniform industry practice. The following authorities are referred to:

“The Art and Science of Modern Innkeeping by Jerome J. Vallen [pages 240-242]

Hotel Accounts and Their Audit by Lawrence S. Fentou, FCA and Norman A. Fowler, FCA published by the The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales:

“Service charges and Tips

Service charges are often levied by a percentage addition to a guest’s bill to represent gratuities to restaurant and room service staff. Sometimes such moneys are paid over to the staff by the hotel via the normal wages system or through the Tronc Master. In other cases staff are paid fixed rates irrespective of the service charges collected, or the or the tariff prices may be inclusive of service charges and VAT. Treatment of service charge income varies with each concern. The auditor should investigate the accounting treatment, and see that the policy is consistent from period to period.”

38.26. Mr. Bhasin, ld. Counsel, refers to a book titled ‘Industrial Relations Wage Fixation Hotels & Restaurants’ which, according to him, provides illustrations and examples of numerous labour awards that have recognized the collection of service charges for over 50 years.

38.27. Reliance is placed upon a prescription by the Wage Board which has uniformly prescribed levy of service charge for all for all hospitality establishments in Delhi. It specifies that the service charge should be imposed within the range of 5-10%.

38.28. The CCPA does not have the mandate to issue directions in the garb of guidelines. The CCPA while doing so, is in effect, exercising parallel authority of District & State Consumer Forums, which is contrary to the scheme of the CPA, 2019 itself. Further, even while issuing an order under Section 20 of the act, the CCPA has to give the party an opportunity to be heard, which has not been done in this case. Thus, the CCPA has no power to pass guidelines in rem and the question as to whether any practice is an unfair trade practice is to be decided by the District Magistrate Forum and not by the CCPA.

38.29. Executive and administrative instructions without the backing of a law cannot be enforced. Reliance is placed on the judgment Amazon Seller Services Pvt. Ltd. v. Amway India Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. & Ors. [(2020) SCC OnLine Del 454] wherein the guidelines therein, were held to not have statutory backing and therefore not enforceable. Further, in the judgment, it was clarified that executive and administrative instructions cannot constitute law.

38.30. Under Section 2(6) of the CPA, 2019, a complaint can only be filed if the price of a commodity exceeds the agreed-upon price between the parties. Therefore, as long as establishments inform customers about the service charge by displaying it on the menu, no complaint can be registered under the CPA, 2019.

38.31. The right to set prices is a managerial function and cannot be interfered with. For example, a restaurant establishment that is air-conditioned or offers live music may charge slightly higher prices. This is the establishment’s right, which cannot be undermined by the CCPA by way of issuing guidelines.

38.32. The present case does not fulfil the parameters of ‘unfair trade practice’ as laid out under Section 2(47) of the CPA, 2019. The basic precondition to constitute an unfair trade practice, under the Act, is for the practice to be for the purpose of promoting the sale, use or supply of any goods or services. However, in the present case, the service charge is not meant to promote sale, use or supply of any service.

38.33. On the ground of the Respondent that GST is being levied on service charge, the same falls within the power of the GST department and GST authorities and the CCPA cannot interfere in this area.

Submissions on behalf of the Respondents:

39. On behalf of the Respondents Mr. Chetan Sharma – ld. ASG; ld. Counsels Mr. Sandeep Mahapatra and Mr, Kirtiman Singh addressed their submissions which are set out below:

39.1. NRAI and FHRAI have merely 1116 and 3000 members respectively whereas tall claims are made in the petition that there are lakhs and lakhs of members. This is a completely incorrect statement.

39.2. There is no restriction or mandate imposed by the authority which restricts the flexibility of establishments to price food products in the manner as they choose. Adequate freedom exists for the establishments to price the food products and other items.

39.3. The freedom guaranteed to the Petitioners under Article 19 of the Constitution of India is not impinged upon. The fundamental argument is that after fixation of the prices of food items, over and above the price of the food products, the consumer cannot be mandatorily asked to pay a service charge.

39.4. Power to ‘Levy’ is a sovereign function, which the establishments cannot usurp to themselves. There is a clear attempt by the establishments to superimpose upon the consumer, over and above the price of the food items, a charge that is being presented as though it were being charged by the Government. Reliance is placed upon Assistant Collector of Central Excise v. National Tobacco Co. (MANU/SC/0377/1972) to argue that the word levy or levying of any tax charge is a sovereign function.

39.5. Paragraph 12 of the writ petition being W.P. (C) 10867/2022 is highlighted to argue that in the said petition, it is the stand of the Petitioner that the service charge is not a tip and the consumer is required to pay the same whereas in the representations made to the Government, the exact opposite was stated by the association itself. Reference is made to the representation dated 2nd June, 2022 where service charge is acknowledged to be colloquially known as the `Tip’.

39.6. The representation dated 24th June, 2022 is relied upon, where service charge is clearly mentioned to be a Tip or a Gratuity.

39.7. On a query from the Court as to what is the source of power of the authority for issuing guidelines, reliance is placed upon Section 18(2)(l) of the CPA, 2019 to submit that apart from the specifically mentioned powers of the authority, the authority also has the power to issue guidelines to prevent unfair trade practice and to protect consumer interest.

39.8. Power of the CCPA can also be read into Section 10 of the CPA, 2019 which clearly sets out four categories of matters which can be regulated by the authority:

- Violation of rights of consumers,

- Unfair trade practices,

- False or misleading advertisements which are prejudicial to the consumer interest,

- To protect, promote and enforce the rights of consumers.

- Violation of rights of consumers,

- Unfair trade practices,

- False or misleading advertisements which are prejudicial to the consumer interest,

- To protect, promote and enforce the rights of consumers.

39.9. The mandate of the CCPA under Section 10 of the CPA, 2019 being so broad, any complaint received from the consumer can be looked into by the authority and steps can be taken under Section 18 of the CPA, 2019. The emphasis is, therefore, on the fact that Section 10 of the CPA, 2019 provides the mandate and Section 18 of the act permits the authority to issue guidelines.

39.10. Hundreds of complaints were received against service charges being levied in the restaurant establishments and the same being collected by the said establishments, the authority could not have just been a mute spectator.

39.11. There is a long background which led to the issuance of these guidelines. Firstly, a letter was sent by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs on 14th October, 2015 to the Hotel Association of India in respect of collection of service charges. In response to the said letter, on 28th October, 2015, the said association took a position that levying of service charge is a globally accepted practice. However, the Hotel Association of India also clearly informed the Ministry that if a consumer is dissatisfied with the experience the service charge can even be waived of. The same is extracted for reference:

“It is also pertinent to note that service charge is completely discretionary. Should a customer be dissatisfied with the dining experience he can/she can have it waived off. Therefore, it is deemed to be accepted voluntarily less than one percent of customers ask for a waiver, further substantiating their acceptance of this practice.”

39.12. The Ministry of Consumer Affairs upon receiving this clarification from the Hotel Association of India wrote to the Food and Civil Supplies Ministry of all State and Union Territories placing the stand of the association on record. The letter further contained a direction to disseminate this position to all the restaurant establishments with a direction that the fact that service charge is voluntary and discretionary for the consumers should be displayed in all the restaurant establishments. Despite this particular communication having been issued, it was realised that the restaurant establishments were charging service charges almost in a mandatory manner. This led to the guidelines dated 21st April, 2017 being issued by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs clearly clarifying that the price of goods ought to cover both the goods and the services and a tip or gratuity is in the discretion of the customer. The said guidelines also prescribe that making a customer leave the premises or subjecting the entry of a customer to the condition of paying service charge would also constitute a restrictive trade practice.

39.13. On 9th March, 2021, after the issuance of these guidelines, again a press release was issued in response to various consumer complaints received across the country. The release clarified that the service charge is optional and that its payment is at the consumer’s discretion.

39.14. The guidelines dated 21st April, 2017 required the establishment to give a bill whenever payment is received. It also required the establishment to put up a board. The service charge column ought to be left blank and discretion should be to the customer. The rights of customers to be heard and redressed was also reserved. The said guidelines which were issued under the Consumer Protection Act of 1986 has stood the test of time and have never been challenged.

39.15. There were various sets of complaints which were received when the consumer helpline was started by the Government. The said complaints raised multiple issues:

- Service charge being made mandatory by the establishments.

- Service charge being touted as a charge being levied by the Government.

- Coercive measures undertaken by the establishments to force the consumers to pay service charge, even when they were dissatisfied with the service.

- Measures such as employment of bouncers etc., being used for collecting service charge.

- No consistency in the amount being charged as service charge. Some establishments were charging 15%, some 12% and some 13%.

- Complaints as to terminology used for service charge was also not uniform and was creating confusion. In the bills the terms being used were VSC, SC, SER, etc.

- Service charge being made mandatory by the establishments.

- Service charge being touted as a charge being levied by the Government.

- Coercive measures undertaken by the establishments to force the consumers to pay service charge, even when they were dissatisfied with the service.

- Measures such as employment of bouncers etc., being used for collecting service charge.

- No consistency in the amount being charged as service charge. Some establishments were charging 15%, some 12% and some 13%.

- Complaints as to terminology used for service charge was also not uniform and was creating confusion. In the bills the terms being used were VSC, SC, SER, etc.

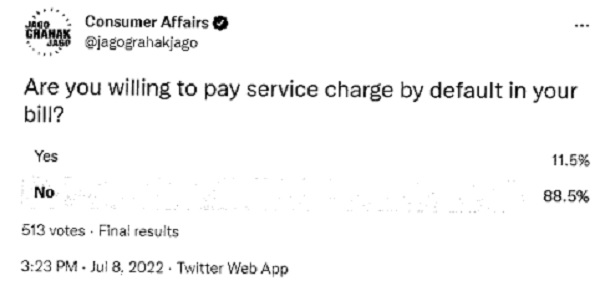

39.16. In response to the large volume of complaints which were received by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, a press release was issued by the Ministry on 2nd June, 2022 raising consumers’ grievances with respect to service charge and sought stakeholder consultation. In response to this press release, one of the associations namely Mumbai Grahak Panchayat also wrote to the Ministry stating that the Government ought to declare collection of involuntary service charge as an unfair trade practice.

39.17. After the press release dated 2nd June, 2022 consultations were held with NRAI and FHRAI. It is after such consultation with consumer organizations and the establishments that the impugned guidelines dated 4th July, 2022 were issued. In order to ensure proper intimation and enforcement of the guidelines, communications were also issued to all the District Collector on 6th July, 2022 to conduct investigation and take action in terms of the Act and submit a report to the CCPA. Thus, the impugned guidelines were not in violation of the principles of natural justice inasmuch as the associations were duly heard.

39.18. The FHRAI simultaneously came up with clear press releases stating that the payment of service charges is voluntary, at the discretion of the customer. Extract from website of FHRAI dated 22nd May, 2022 and 2nd June, 2022 are relied upon. These press releases would show that the stand of the FHRAI is that service charge can be removed from the bill and it is the complete discretion of the customer. Thus, the impugned guidelines are fully justified.

39.19 One of the Petitioners’ arguments is that the Tourism Ministry has approved the mandatory collection of service charges. However, FHRAI’s writ petition states that the Consumer Affairs Ministry wrote to the Tourism Ministry, and in response, the Tourism Ministry clarified that its guidelines do not mandate the collection of service charges.

39.20. Both the Petitioners have not filed any agreement on record which reflects that employees’ associations or labor unions have confirmed service charges as part of an agreement with the employers.

39.21. Concerns are raised by the Union of India as to the manner in which the money which is collected as service charge is used by the establishment. Whether the same is even disbursed to the employees or not. If the service charge is being seen as beneficial provision under labour law, then some proof ought to have been adduced that the same is being paid to the labour and the employees.

39.22. There is no consistency between the NRAI and the FHRAI as to whether service charge is a tip or a gratuity. The consultation process which took place in May and June, 2022, FHRAI issued fresh releases contemporaneously to show that service charge is voluntary and not mandatory. It can therefore be waived off. It is because of this reason that the guidelines say that service charge is voluntary.

39.23. An attempt has been made to distinguish all the three judgments relied upon by the Petitioner. As far as Amazon v. Amway (supra) is concerned, reliance is placed upon the decision in Poonam Verma v. Delhi Development Authority [(2007) 13 SCC 154] wherein it is held that guidelines are not binding only if they lack the statutory backing. Here the guidelines are fully backed by Section 18 of the CPA, 2019.

39.24. Insofar as S.S. Ahuja v. Pizza Express (supra) is concerned, the MRTP proceeded on the basis that the tourism ministry had approved the service charge on the menu charge. However, the Ministry in the present case, has confirmed the opposite.

39.25. In Nitin Mittal v. Pind Balluchi Restaurant (supra) the issue of pricing arose in the context of differentiation between the dining charges and take-away charges and only in that context, the MRTP had held that service charge can be levied.

39.26. Insofar as the word ‘levy’ is concerned, it is argued that levy means an approval from the Government for a sovereign function. Reliance is placed upon the decision of Krishnakant Sakharam Ghag v. Union of India and Ors., W.P.(C) 4839/2003 dated 3rd March, 2006 passed by the ld. Division Bench of the Bombay High Court.

39.27. The Respondents do not object to the price of goods being as per the discretion of the restaurant establishments but anything above the price of goods as service charge would not be permissible.

39.28. It is also highlighted that in at least three countries i.e., Mexico, Switzerland and U.S., tip or gratuity is a voluntary service fee.

39.29. The consumer protection helpline receives a large quantum of complaints in respect of service charge and a chart in this regard has been placed before the Court to confirm that more than 10,491 complaints have been received on the national consumer helpline in respect of service charges. It is thus submitted that the guidelines ought to be upheld and the writ petitions deserve to be dismissed.

39.30. It is further submitted by him that Section 10 and Section 18(2)(l) of the CPA, 2019 confers the power on the Authority to issue these guidelines. Thus, the said guidelines have been issued after a broad-based consultation with the stakeholders.

39.31.It is also further impressed upon the Court that service charge after being added to the regular bill amount is also a component over which GST is being charged. Therefore, in effect, the consumer is being forced to pay a substantially higher sum than just the charges for the food that has been consumed by the consumer in the establishment.

Analysis:

I. Evolution of Consumer Protection Law in India – Jurisdiction of the Central Consumer Protection Authority

40. Caveat Emptor— ‘let the buyer beware’ was historically, the principle of caution to buyers of goods. Subsequently, in the United States, the doctrine of Caveat Venditor— ‘let the seller beware’ developed which imposed greater obligations on sellers.1

41. In Common law jurisdictions, the mutual obligations of buyers and sellers were governed by laws relating to the sale of goods. Further, any dissatisfaction of the consumer in respect of a product or service could be adjudicated as a tortious claim.

42. However, the realities of the markets, the modes of conducting trade have all undergone enormous change in the last 40 to 50 years resulting in the statutory codification of consumer protection law. Laws were enacted across the globe, for protection of consumer rights.

43. In India, the first consumer protection legislation is the Consumer Protection Act of 1986 which was a law enacted for better protection of the interest of consumers. This was sought to be effected by establishment of consumer councils and dispute redressal forums at the District, State and Central level. The law of 1986 saw the rise in consciousness amongst consumers of their rights and there was a proliferation of consumer cases across the country over the next two decades.

44. The Act of 1986 was further amended in 2002 which made some changes in the pecuniary jurisdiction of consumer redressal forums and contemplated the creation of Benches for State and National consumer Commissions. In the amendment in 2002, one of the important additions was the inclusion of services and service providers into the ambit of the law. Over the next few years, consumer cases in respect of products as well as services saw a substantial increase.

45. The growth of the internet also changed the manner and mode of sale and purchase. E-commerce platforms came to be established and other methods of selling such as direct selling, telemarketing, multilevel marketing also became quite prevalent. In order to deal with the challenges that consumers were facing in the new marketplace which included brick and mortar shops, shopping arenas, wholesale malls, retail malls, e-commerce platforms, multilevel marketing and telemarketing platforms, etc., a need was felt for enacting a new law for protection of consumer rights.

The Consumer Protection Act, 2019

46. The CPA, 2019 was then enacted to address challenges of the new markets. The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the 2019 Act recognizes the need for creation of an authority to protect consumer interest, in the following terms:

“4. The proposed Bill provides for the establishment of an executive agency to be known as the Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) to promote, protect and enforce the rights of consumers; make interventions when necessary to prevent consumer detriment arising from unfair trade practices and to initiate class action including enforcing recall, refund and return of products, etc. This fills an institutional void in the regulatory regime extant. Currently, the task of prevention of or acting against unfair trade practices is not vested in any authority. This has been provided for in a manner that the role envisaged for the CCPA complements that of the sector regulators and duplication, overlap or potential conflict is avoided.”

47. The CPA, 2019 is, thus, a statute which has been enacted for the purpose of protecting the interest of consumers in the modern world. Some of the provisions of CPA, 2019 insofar as they are relevant for the adjudication of the present two writ petitions are discussed hereinbelow:

i. Section 2(4) of the CPA, 2019 defines ‘Central Authority’ as the Central Consumer Protection Authority established under Section 10 of the Act.

ii. Section 2(7) of the CPA, 2019 defines ‘consumer’ as a person who either buys any goods for consideration or avails any service for a consideration.

iii. Section 2(9) of the CPA, 2019 defines ‘consumer rights’ as rights of a consumer. This provision includes the right of a consumer to be informed about the price of goods so as to insulate the consumer against any unfair trade practice. Such rights also include the right to consumer awareness. This provision is of utmost relevance for deciding the present issue and the same is extracted below for ready reference:

“Section 2(9) “consumer rights” includes,—

xxx xxx xxx

(ii) the right to be informed about the quality, quantity, potency, purity, standard and price of goods, products or services, as the case may be, so as to protect the consumer against unfair trade practices;

xxx xxx xxx

(iv) the right to be heard and to be assured that consumer’s interests will receive due consideration at appropriate fora;”

iv. Under Section 2(19) of the CPA, 2019 the term ‘establishment’ is defined. It includes any entity which carries on a business, trade, profession or any work incidental thereto.

v. Section 28 of the CPA, 2019 defines misleading advertisement inter alia as an advertisement which deliberately conceals important information.